There’s a column in the New York Times called “By the Book,” in which successful writers—or famous people who have written a book, which isn’t quite the same thing—answer questions about their reading habits. If my friend Donna reads an example she particularly likes, she cuts it out and shares it with me over coffee. We are both delighted when writers mention a book we’ve actually read, and we love running into the titles of beloved children’s books (Charlotte’s Web seems to come up quite often). But what we search most diligently for in the column is a mention of Middlemarch. This has become a running gag—well, we think it’s funny, anyway.

There are many typical “By the Book” questions that can lead to the answer ‘Middlemarch,’ such as ‘What book are you embarrassed not to have read yet?’ or ‘What’s the last great book you read?’ Donna and I have seen Middlemarch come up in response to a surprising variety of questions, although I don’t think it’s yet emerged as a ‘favorite book no one else has heard of’ or a ‘guilty pleasure.’

My own experience with Middlemarch would put it in “By the Book’s” category ‘a book no one should read before the age of forty.’ My college major was “the history and literature of England,” and I read Middlemarch not once, but twice, before the age of 21. The ‘twice’ is because I had no memory of my first reading. It would be false to say the story hadn’t stayed with me. The truth was that it never penetrated my consciousness in the first place. That wasn’t because of its length—I’ve always loved Charles Dickens, and many of his books are just as long—but because of its subject matter.

At the start of Middlemarch, its heroine Dorothea Brooke, a naïve and idealistic teenager in an English village in the 1830s, goes happily into a marriage with a deeply unattractive and boring old man. That’s where my brain disconnected. I didn’t get beyond that point, because I simply couldn’t believe anyone could be so stupid. After all, I was a naïve and idealistic teenager myself in those days—but unlike poor Dorothea, a teenager who knew what sex was and what role it played in a happy marriage. Dorothea’s ignorance was inconceivable to me, and that seems to have robbed the rest of the book of meaning, even after two readings. I remember wondering how Middlemarch could be classified by so many scholars as the greatest English novel of all time.

Many years later, I decided to start over. This time, I bought Middlemarch as an audiobook and listened to all thirty-two hours of it, while I folded wash, cooked dinner, watered plants, and took walks. It turns out the book is about not one but two terrible marriages, and this time around it wasn’t boring but heartbreaking, as I watched two optimistic young adults take one step after another into tragedy. I now found motherless Dorothea’s bad decision realistic (especially for a woman living in the nineteenth century), and the young doctor Tertius Lydgate’s deluded progress into a loveless marriage with Rosamunde Vincy only too plausible.

This summary of the novel does it no justice—it’s much richer and more complicated than this, full of subtle social commentary and sub-plots involving countless other characters who must also make difficult moral decisions. This isn’t meant to be a review of Middlemarch, however, but a reflection on how judgements about books can evolve. I’ve been talking about a change for the better here, but over the past twenty years it’s happened to me much more often that I’ve reread a book I remember loving in my twenties, only to find it overwritten or silly or sadly outdated. Look at The Catcher in the Rye. As far as I’m concerned, no one who read it in their teens should ever bother to read it again.

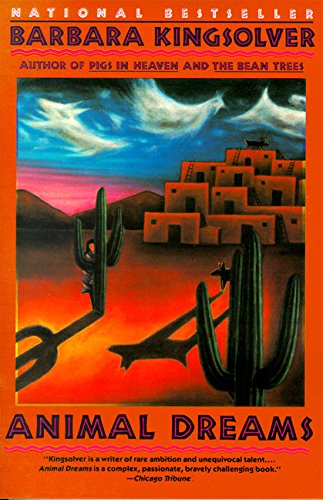

Which just goes to remind us how precious the novels are that we can reread throughout our lives and still lose ourselves in. We greet the beloved characters with a smile of recognition, laugh at the well-known funny bits, cry yet again at the touching scenes, and appreciate the clever plotting even though we already know exactly what’s going to happen. For me, one of these eternal books is Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal Dreams (1990), which moved me deeply when I first read it and has continued to twist my heart with every reading since.

Anybody else have examples of books outgrown, grown into, or still worth reading every ten years or so? Please share them.

What an interesting post! And, YES, I had this negative experience with a book I read as a child, which seemed to me at the time the ultimate story of passionate pursuit of personal freedom despite difficult social and economic circumstances. Upon re-reading it last year I was rather horrified to find it depressing, tragic, reeking of defeat, and quite possibly racist. I am too embarrassed to even admit the title of the book, feeling that even now I have not really understood it. I just know I had a TOTALLY different reaction to it!

Am enjoying your posts – I went to F&W with Natasha!

LikeLike

Hi Ellen! Natasha told me who you are–I’m a fan of F&W without ever having been there! As for your experience with this book you loved, this kind of thing happens to me a lot. We change, the times change, and something we remember loving now seems ridiculous or even, as you say, racist. I only gave one example, but I could give twenty. Still, I think we have to remember to judge books within the context of when they were written, if we can.

I’m so glad to hear you’re enjoying my posts. I hope by this time next year you’ll be able to enjoy my book. Have a good weekend.

LikeLike

So true – I guess it’s hard to really see all that change as it’s happening, and sometimes things happen that smack you in the face with just how much time has gone by.

🙂 So exciting about your book coming out – BEST OF LUCK with it!!!!!

LikeLike

I have many, many books that I read over and over again and can even open them to any radneom page and enjoy it, even though I know exactly what is going to happen. Some are children’s books and some are adult. Examples include Pride and Prejudice, many of Dorothy L. Sayer’s or Josephine Tey’s books, anything by Robertson Davies, the Miles Vorkosigan series by Lois McMaster Bujold, and…well, I could go on for quite a while. I have had one or two books that I read as a child and didn’t get that I read later and loved. An example is Dune, which seemed awfully confusing when I was in 7th grade.

However, I have also had books that I read as a child, could not understand at all, that I read as an adult, and STILL could not understand, let alone, enjoy. The book, Kim, by Rudyard Kipling is an example–and I’ve tried it as a child, a young adult and as an older adult. I kept trying because it is supposed to be one of the English novels. Great novel in the sense of “great bore” and “great puzzlement” would be a lot closer to the truth, in my opinion!

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment! I haven’t tried “Kim” in a long time, but I don’t remember liking it either, and I was disappointed because I loved “The Jungle Book.” The book, I should add, not the Disney movie, which I’ve never liked.

LikeLike