Today, the first of August, is the Swiss equivalent of the Fourth of July, similarly celebrated with picnics, firework displays and speeches by local and national politicians. Swiss families gather with their neighbors at village-sponsored breakfasts or evening fish fries, and the huge bonfires lit on local hills are visible for miles. Already for days now, a band of pre-teens in my neighborhood has been setting off little popping firecrackers known as “lady farts.” It’s a good thing they’ve been having their fun early, because today, the actual holiday, is expected to be chilly and rainy all day.

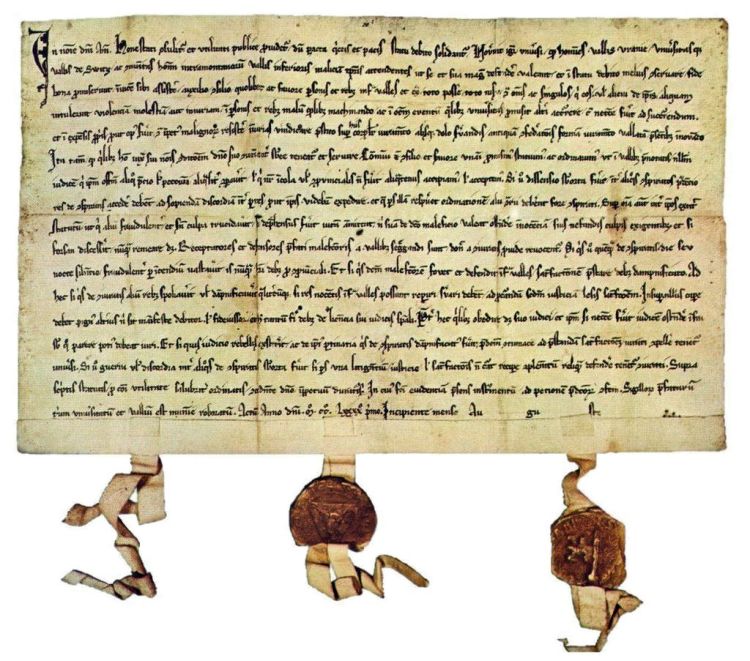

Apparently, July 4, 1776, actually was the day that the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, and a mob really did storm the Bastille prison on July 14, 1789, the day the French celebrate as the beginning of their revolution. But when it comes to Switzerland’s August 1, well…it’s actually just a convenience. In 1891 the federal government picked it as a good day to commemorate a medieval event: that three small German-speaking states in the middle of the Alps agreed to help each other fight again their Hapsburg overlords. By the time these territories, Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden, had formed a loose military alliance, the Battle of Morgarten (1315), the first successful Swiss fight against Hapsburg troops, had already taken place. Perhaps the late-nineteenth-century-bureaucrats decided that celebrating a battle was too blood-thirsty. In any case, they chose to predate Switzerland’s founding all the way back to 1291, when a perfectly ordinary document confirming an already existing agreement between local bigwigs in Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden was signed.

All of this became the basis of a myth: that three great freedom-loving warriors from the original cantons stood on the shores of Lake Lucerne and swore a sacred oath, with swords in hand: to liberate their lands from their “foreign” oppressors. Called confederates in English, the Swiss-German word for these allies is much more powerful: they are “oath comrades” or Eidgenossen, and Switzerland still calls itself an Eidgenossenschaft, a union of companions who have sworn loyalty to each other. Which perhaps explains why there was relatively little fuss when a large chunk of French-speakers in the Jura mountains broke away from the canton of Bern and formed their own canton, Jura, in 1979. After all, it wasn’t Bern those citizens owed ultimate loyalty to, but rather the Eidgenossenschaft, their band of national oath brothers.

Once they’d won the Battle of Morgarten, the three territories in that original union didn’t remain alone for long. By 1353 they’d been voluntarily joined by Bern, Lucerne and Zürich, while the future cantons of Glarus and Zug had been conquered (hmm, perhaps I should say they’d been liberated.) Fighting against the overlordship of the Hapsburgs continued into the fifteenth century; then there was territory to be won from the Burgundians to the west, the Swabians to the north, and the Milanese to the south. All this conquering and treaty-signing eventually created a confederation of thirteen territories (there were no cantons then) that lasted until Napoleon conquered Switzerland in 1798. Switzerland’s current boundaries, with its full complement of cantons (not counting Jura), finally came into being in 1848, which is when the union became a federal state with a constitution.

Why doesn’t our national day commemorate signing the constitution on September 12, 1848? That’s probably the subject of lots of scholarly articles—I’ll just say that the legend of the warriors on the meadow makes a better story, even if it is fake news. In defense of the honor of the Swiss government, I should add that its website is quite scathing about the so-called federal charter of 1291, stating that it “certainly did not amount to a revolutionary act of self-determination by the peasantry, but rather secured the status quo in the interests of the local elites.” Still, most Swiss prefer to go along with the mythical medieval swearing ceremony, known as the Rütlischwur, which makes for a much more dramatic painting.

I was curious to find out if other countries had national days celebrating events as old as Switzerland’s. Not many, it turns out. Most Latin American countries celebrate their freedom from Spain (or, in the case of Brazil, Portugal) in the early 1800s, and most African countries their liberation during the twentieth century from whichever European power held them as a colony. Other countries recognize their freedom from the Soviet Union; Germany celebrates its reunification in 1990. I was impressed to see that the Maldives’ national day commemorates their freedom from Portugal in 1573, and Sweden celebrates the election of King Gustav Vasa on June 6, 1523. Still, I continued to assume that the Swiss held the record for the oldest date until I got to the Faroe Islands. Their national day recognizes the death of King Olaf II of Norway, who brought Christianity to the Islands. Saint Olaf’s Wake, as July 29 is called, memorializes an event that took place in 1030. Wow! That topped my list until I read that Japan celebrates its founding by Emperor Jimmu, which happened on February 11, 660 BC! Never mind that Jimmu is a mythical emperor. Japan still wins!

I’d like to add a final note about the Swiss national anthem, which is a hymn thanking God for a beautiful country full of pious people. The song goes back to 1841, with words as old-fashioned as you’d expect. The Swiss are no longer particularly devout Christians—only 27% say they go to church at least once a month. Still, as national anthems go, this one is really not bad; at least it’s free of blood and war. The problem with it is that no Swiss under seventy seems to know the words. Most people can manage the first two lines about the sun rising over the Alps, and after that they start to mumble. This is particularly apparent at soccer matches, where national anthems are regularly played in honor of the opposing teams, and players are expected to line up on the field and sing enthusiastically before playing ball. The Swiss are surely not the only ones who fumble for words, but our athletes seem to be especially bad at faking it; most of them don’t even bother to move their mouths. They take a lot of flack for this, but, hey, at least they’re honest about their ignorance, which is more than can be said about a lot of so-called patriots around the world.

They also made it into the quarter finals in this year’s European Championship, which is as far as any Swiss team has gotten since 1954. So who cares if they don’t sing? They know how to play soccer.

Happy Swiss National Day, Kim. You picked a wonderful country to adopt and love!

LikeLike

Thanks, Betsy. I feel that way, too–very lucky to live here.

LikeLike

I always enjoy history and you always write in an interesting and humorous way!

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Kim,

I loved this one too. You’re a good history professor! . . . As you can see, I’m catching up on a number of old emails.

Love to all, -Bob

>

LikeLike

So glad you enjoyed this, Bob. I realized after I wrote this that while I was talking about reality versus myth in Swiss history I should have brought up Wilhelm Tell shooting the apple off his son’s head. It’s such a great story–and it’s totally made up.

LikeLike